Summary:

- Essential plant nutrients are necessary for healthy plant growth. The 17 essential plant nutrients are C, O, H, N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Fe, B, Ni, Cu, Mo, Z, Cl, and Mn.

- Essential plant nutrients may be categorized as structural (C, O, H), primary macronutrients (N, P, K), secondary macronutrients (Ca, Mg, S) or as micronutrients (Fe, B, Ni, Cu, Mo, Z, Cl, Mn).

- Detecting plant nutrient deficiencies may be done by getting a soil test (for some nutrients) or by assessing both the location and appearance of deficiency symptoms on a growing plant.

- Deficiencies of mobile nutrients appear in older leaves, whereas deficiencies of immobile nutrients appear in younger leaves.

- Treating nutrient deficiencies is important to ensuring proper plant growth and functioning, but fertilization should be done correctly with the right type and quantity of fertilizer.

- The most commonly deficient nutrients are the primary macronutrients N, P, and K, but soil fertility challenges are often unique based on soil type and location.

Outline:

- What are the different types of plant nutrients?

- How is each nutrient categorized, and what purpose(s) do certain plant nutrients serve?

- How can I identify nutrient deficiencies?

- Why is it important to identify and treat nutrient deficiencies?

- What nutrients are commonly deficient in the soil?

I’m sure you are familiar with the concept of nutrients. Nutrients are those elements, minerals, and compounds that, “provide nourishment essential for growth and the maintenance of life.” (Thanks, Oxford Languages.)

You ingest a variety of foods to meet the nutritional demands of your body. You can go out and seek these nutrients from many different places in many different forms. Plants, on the other hand, rely on their environment to supply them with the nutrients they need. Their access to nutrients is limited to the soil in which they’re planted. Supplying plants with the right quantities of nutrients is essential to healthy plant growth, but there’s more to it than simply fertilizing every so often.

In this post, we’ll explore what nutrients are considered “essential” and what they do for plants.

What are the different types of plant nutrients?

There are 17 essential plant nutrients (though nickel is not always listed as an essential nutrient, depending on what you read), and they may be divided into categories depending on the quantity in which the plant needs them.

The terms “macronutrient” and “micronutrient” are common in fertilizer recommendations and product descriptions. They simply describe the quantities of these nutrients that are demanded by plants. “Macro-” means “big” and “micro-” means small, so macronutrients are needed in relatively large quantities, whereas micronutrients are needed in relatively small quantities.

I like to add a little more context when describing plant nutrients, as is common in horticulture. Essential plant nutrients may be divided into four categories:

Structural Nutrients: C, O, H

These nutrients make up 90% of a plant’s mass. They are readily available in the soil and atmosphere and don’t require additional supplementation by you.

Primary Macronutrients: N, P, K

These nutrients are needed in large quantities by plants and often require supplementation. Deficiencies of these nutrients are common.

Secondary Macronutrients: Ca, Mg, S

These nutrients are needed in large quantities by plants but to a lesser extent than primary macronutrients. Deficiencies of these nutrients are less common but are more common in some places than others.

Micronutrients: Cl, Fe, Mn, B, Z, Cu, Ni, Mo

These nutrients are needed in small quantities by plants, and deficiencies are not as common as macronutrient deficiencies.

The 17 essential plant nutrients all fall into one of these categories.

How is each nutrient categorized, and what purpose(s) do certain plant nutrients serve?

There are three structural nutrients, three primary macronutrients, three secondary nutrients, and eight micronutrients.

Structural Nutrients

| Nutrient | Primary Source | Primary Purpose(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon – C | CO2 (carbon dioxide) in air | Plant growth & functioning |

| Oxygen – O | CO2 (carbon dioxide) in air | Plant growth & functioning |

| Hydrogen – H | H2O (water) in soil | Plant growth & functioning |

Primary Macronutrients

| Nutrient | Primary Source | Primary Purpose(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen – N | NH4+ (ammonium) or NO3– (nitrate) in soil solution | Leafy growth development, photosynthesis |

| Phosphorous – P | PO43- (phosphate ion) compounds in soil solution | Energy transfer (carbohydrates from leaves to flowers/fruit) |

| Potassium – K | K+ (potassium ion) in soil solution | General health & functioning |

Secondary Macronutrients

| Nutrient | Primary Source | Primary Purpose(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium – C | Ca2+ (calcium ion) in soil solution | Growth stimulation, root & leaf development |

| Magnesium – Mg | Mg2+ (magnesium ion) in soil solution | Photosynthesis, respiration |

| Sulfur – S | SO42- (sulfate) in soil solution | Protein formation |

Micronutrients

| Nutrient | Primary Source | Primary Purpose(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorine – Cl | Cl– (chlorine ion) in soil solution | Water balance |

| Iron – Fe | Fe2+ (ferrous) or Fe3+ (ferric iron) in soil solution | Photosynthesis, respiration |

| Manganese – Mn | Mn2+ (manganese ion) in soil solution | N transformations |

| Boron – B | H2BO3– (dihydrogen borate) in soil solution | H2BO3– (dihydrogen borate) in soil solution |

| Zinc – Z | Zn2+ (zinc ion) in soil solution | N transformations |

| Copper – Cu | Cu+, Cu2+ (copper ions) in soil solution | Photosynthesis & metabolism |

| Nickel – Ni | Ni2+ (nickel ions) in soil solution | Nitrogen uptake |

| Molybdenum – Mo | MoO42- (molybdate) in soil solution | Nitrogen uptake |

For more information about the specifics of these nutrients, check out these excellent articles (but keep in mind that much information about deficiencies and nutrient quantities in native soils is extremely location-specific!):

Washington State University Wheat & Small Grains – Mobility of Macronutrients in Plants.

Explains macronutrient functions and mobility within plants.

Washington State University Wheat & Small Grains – Micronutrient Functions in Plants. Explains micronutrient functions in plants in greater depth.

Alabama A&M and Auburn Extension – Essential Plant Nutrients.

Explains essential plant nutrient functions and deficiency symptoms.

How can I identify nutrient deficiencies?

There are multiple ways to identify nutrient deficiencies, but your method of choice may depend on what you have available to you.

Before you even sow a single seed, you can identify some nutrient deficiencies by getting a soil test. Soil tests are often offered by university extension services. You can also send them in to professional soil testing laboratories, but this is often more expensive.

After your plants have begun growing, you may be able to identify nutrient deficiencies just by analyzing the appearance and location of plant nutrient deficiency symptoms.

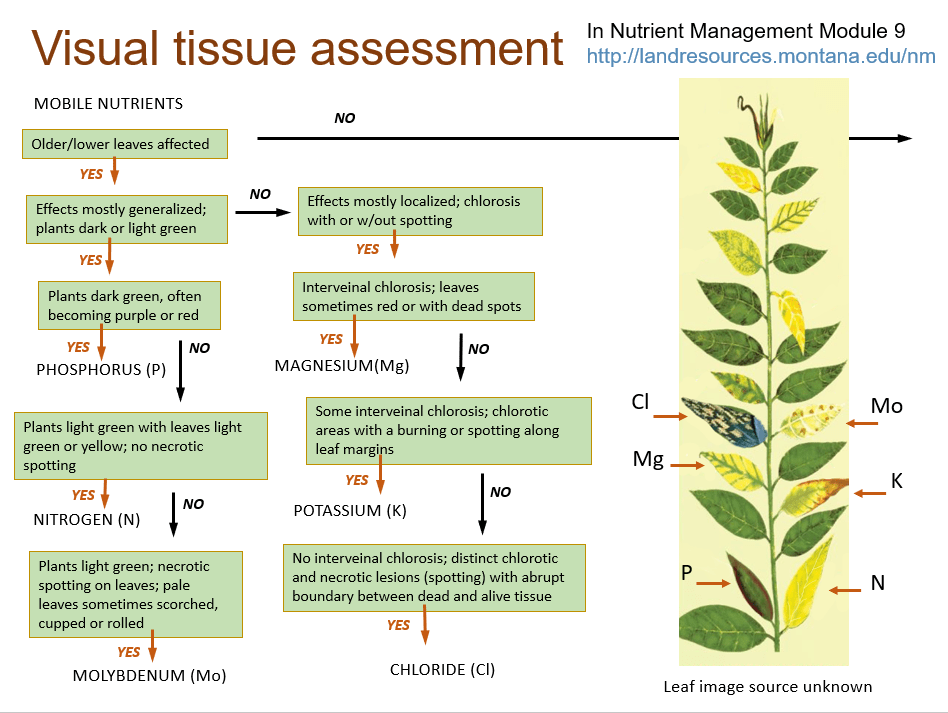

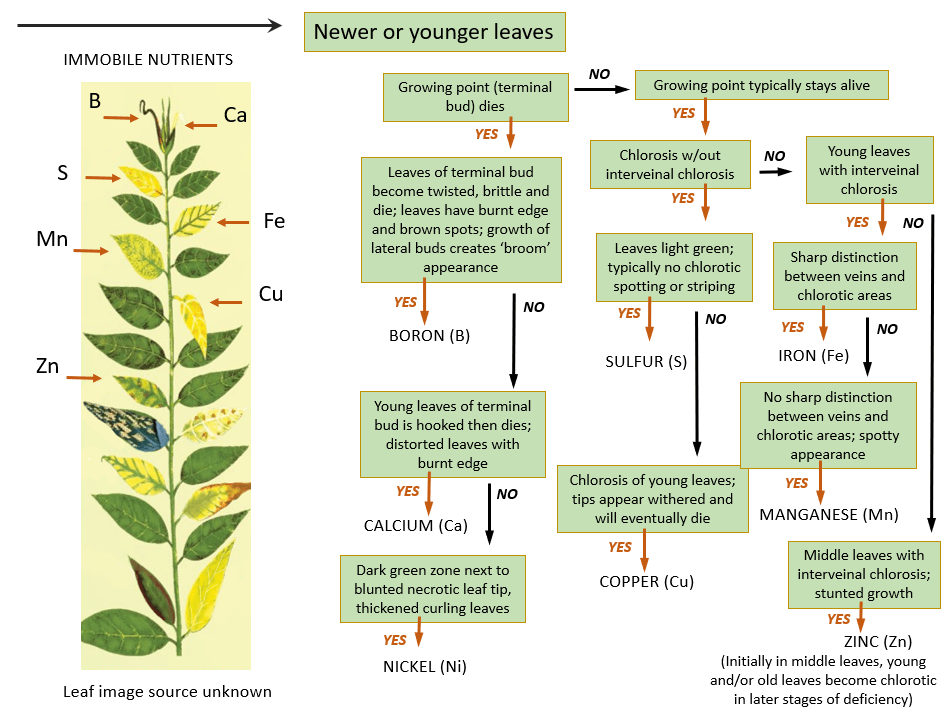

It is important to note the location of nutrient deficiency symptoms because nutrients are either mobile or immobile in plants. Mobile nutrients may be moved around within the plant, translocating deficient nutrients from old growth to new growth. Essentially, the plant can harvest nutrients from itself to supply new growth with enough nutrition. Deficiencies of mobile nutrients therefore occur in older leaves. Immobile nutrients cannot be moved within the plant, so deficiencies of immobile nutrients appear in new growth.

Montana State University created an excellent, easy-to-follow flow chart for diagnosis of common nutrient deficiencies. First, you must choose whether the deficiency occurs in older or newer growth to determine if it is an immobile or mobile nutrient that is deficient. The questions become more specific regarding the appearance of the deficiency symptoms:

You can access this image and a drop-down version of this flow chart on Montana State Univeristy’s Website:

Montana State University – Nutrient Deficiency and Toxicity

Identifying nutrient deficiencies takes practice. Sometimes, nutrient deficiency may be confused with a plant disease or toxin. You can double-check your hypothesis by getting a plant tissue test from a laboratory, but this can be expensive and unnecessary. Sometimes, it’s easiest to treat a suspected nutritional deficiency with the proper fertilizer and see if the problem resolves. If not, it’s likely something else requiring further investigation.

Why is it important to identify and treat nutrient deficiencies?

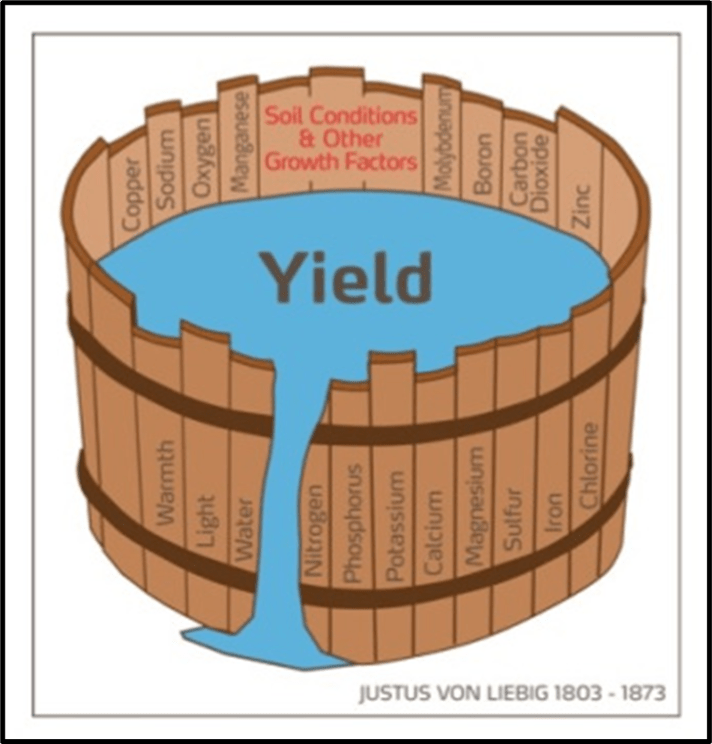

The nutrients discussed in this article are all essential to plant growth, meaning that plants cannot function and grow properly without them. A lack of just one essential plant nutrient may affect a plant’s ability to grow larger, create flowers and roots, or even survive, no matter the quantity of other nutrients in the soil. This principle is known as Liebig’s Law of the Minimum.

Liebig’s Law of the Minimum states that plant growth is controlled not by the total amount of resources available, but by the most limiting resource. In the image at left, plant yield (or growth) is illustrated as water inside a barrel. Essential nutrients and growth factors are represented as individual staves of the barrel. The height of the staves represents the potential yield or growth. If any one stave is too short, the water spills out of the barrel, thus limiting the yield to match the quantity of the most limiting nutrient or growth factor.

Because plant growth is limited by the least available plant nutrient, it is important to treat nutrient deficiencies quickly. Prolonged nutrient deficiencies may cause stunted growth, poor development, lack of flowers or fruit, or even plant death.

However, it is also important to fertilize correctly. Soil testing can help reveal nutrient deficiencies and provide guidance regarding the proper types and quantities of fertilizer to apply. Overapplications of fertilizer wastes money and may pollute the environment with excess nutrient runoff. Sometimes, overapplication of fertilizer may even hinder plant growth (e.g., lodging due to excess nitrogen).

What nutrients are commonly deficient in the soil?

Soil fertility varies widely depending on your location and soil type. Generally speaking, soils that are low in organic matter and have a coarse texture (sands, sandy loams, etc.) will struggle with nutrient retention because they have minimal places to store nutrients.

It is common for soils to lack sufficient quantities of the primary macronutrients nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium. This is because these nutrients are either used by the biota in the soil or they leave the soil via volatilization (off-gassing), leaching, or are otherwise inaccessible to plants.

Near Pittsburgh, PA, where I’m located, it is the primary macronutrients, plus one secondary macronutrient (magnesium), which are commonly deficient in our native soils (Penn State Extension – Managing Soils). I encourage you to seek out resources pertinent to your own soil where you live for more information.

Soil pH can also influence nutrient availability. Nutrient availability is different from the quantity of a nutrient present in the soil. Nutrient availability describes the ability of a plant to access a given nutrient provided that it is present within a soil. The influence of soil pH will be discussed further in another article, but for know, it is sufficient to know that high soil pH levels (above ~7.5) hinder micronutrient availability, and low soil pH levels (below ~5.0) hinder macronutrient availability and present the potential for toxic levels of certain micronutrients.